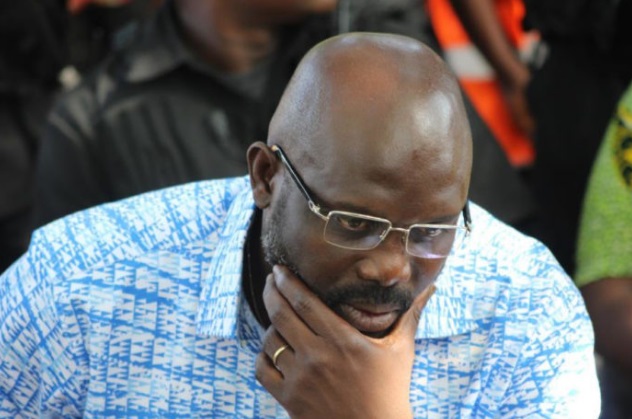

MONROVIA – When former football star George Weah won Liberia‘s presidential election in 2017, he promised to make “transforming the lives of all Liberians” the “singular mission” of his presidency.

But as he marked two years in office on January 22, some of the poor and young voters who assured Weah’s landslide victory said their economic woes have worsened under his leadership, with critics laying blame on government incompetence and failure to tackle corruption.

“I urge the president to listen to the voices of the poor people who made him president today,” said Mark Williams, 23, who runs a store selling typewriters in the capital, Monrovia.

“People believed that if we make this man a president he will look after the poor people. He knows what it means to be struggling or to suffer in life,” he continued, referring to Weah’s birth and childhood in a Monrovia slum before he found international fame as one of the world’s top footballers in the 1990s.

“We agree that the government took over a broken economy but it has to take on its own responsibility.”

Weah inherited an economy badly hit by a slump in global prices of rubber and iron ore – Liberia’s key export commodities. The Ebola crisis of 2014-2016 exacerbated the economic stagnation in the West African nation, where some 80 percent of the population live on less than $1.25 a day. The president promised to turn the economy around by fighting corruption, increasing foreign investment and creating jobs for the poor.

But two years into his six-year term, he has little to show, according to a Liberian civil society group that tracks Weah’s performance against his pledges.

‘No tangible action’

In a January 20 report, Naymote Partners for Democratic Development said the president had fulfilled only seven of his 92 promises, of which five had been completed during his first year in office. These include revising the national school curriculum, passing a long-awaited land rights law and capping the salaries of senior government officials at $7,800.

There were “no tangible actions on promises around accountability and anti-corruption”, the group said, explaining that those pledges included setting new rules to prevent public sector graft and pursuing legal action against companies involved in bid-rigging and other corrupt practices.

As the economy worsened with inflation hitting 30 percent and civil servants reporting months-long delays to salary payments, more than 10,000 people took to the streets in protest last June. Thousands of people rallied once again in Monrovia on January 6, before being dispersed by police using tear gas and water cannon.

The government was also rocked by a scandal in which newly printed Liberian banknotes worth some $100m were reported missing. An investigation later said the allegations were unfounded but revealed the country’s central bank ordered the new currency before seeking permission from the legislature and even after it obtained the necessary approvals, received and paid for more notes than the agreed amount.

“Weah underestimated that playing football is different from running a country,” said Robtel Neajai Pailey, a Liberian political analyst. “He lacks the traditional skill set of a president but has the popular mandate to get himself a good team. Instead he has allowed himself to be advised incorrectly.”

She added: “Liberians have become so politically engaged. They feel the need to go out and protest, to demand that things change, because it’s hitting them where it matters most – their pockets.”

‘Give me small chance’

In a Facebook post on his second anniversary in office, Weah acknowledged the growing discontent, saying “the journey hasn’t always been an easy one” and called for “unwavering and unflinching support”.

On Monday, in his annual address to Liberia’s legislature, the president spoke about the economy, saying “the domestic macroeconomic environment was difficult in 2019 … characterised by low economic growth of less than one percent, annual inflation of more than 20 percent and depreciation of the Liberian dollar by more than 20 percent”.

But he said inflationary pressure had been contained, declining from 30.6 percent in mid-2019 to 25.8 percent at the end of the year. In order to address macroeconomic challenges, the government also secured $213.6m in support from the International Monetary Fund, he said, and launched structural reforms to reduce the bloated wage bill and bring public expenditure under control.

Weah also pledged “to continue to intensify the fight against corruption, which remains prevalent in our society” and announced new legislation to grant Liberia’s Anti-Corruption Commission more prosecutorial powers.

Addressing the Liberian people, he said: “I sense your impatience … And so I ask you to bear with me, and, as we say in our Liberian way: ‘Give me small chance, yah, so I can fix it’.”

Eddie Jarwolo, executive director of Naymote, said Weah’s government needed to be more transparent in its dealings if it wanted to improve its public standing.

“The government is so built on secrecy,” he said. “Accountability and transparency will help boost the economy. But people feel that the government does not want to focus on these promises because the government itself is not transparent. It doesn’t want to be accountable to anybody.”

On the streets of Monrovia, despite disappointment with Weah’s record so far, some of the president’s supporters appear willing to give him the chance he asked for, saying they hoped he would encourage more investment and create jobs.

“I voted for George Weah because I wanted change,” said 46-year-old Evelyn Ross, who makes a weekly profit of $5 by selling fried doughnuts and cold drinks.

“I wanted life to be better but unfortunately things have turned on the other side. I think the president is doing well but if he can invite other companies to come and create jobs, things will be better.”

Terence Karbedeh, a 32-year-old who makes a living from delivering water, agreed: “President George Weah needs to buttress the effort to bring in more investors so that the young people will get jobs and be able to work to help our families.”

Note this article was written by Lucinda Rouse, and first published on 28 Jan 2020, two years into Weah’s presidency.