An opinion by Dr. Ambrues Monboe Nebo Sr. (D.Sc.)

Abstract

From a different angle, this study draws the attention of African leaders to the lesson that must be learned from the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war as it relates to the exacerbating effects of food insecurity in Africa. It employs a qualitative approach with an emphasis on content analysis of relevant literature reviews from the Google Scholar Search Engine and Bielefeld Academic Search Engine.

The paper makes the case for a paradigm shift in Africa’s strategies in use to address food insecurity. It argued that Africa needs to move away from dependency syndrome seen as part of its strategies to address food insecurity because of the implications for political instability.

Considering its geographical advantage so enriched with natural resources, the paper doubts not the potential for Africa to shift the paradigm of addressing food insecurity. The paper concludes that in order to shift the paradigm, African leadership must demonstrate a high level of political commitment or political will.

As a recommendation, making wise use of the geographical advantage will substantially reduce the too much dependency syndrome.

Keywords: Africa, Dependency syndrome, Food insecurity, paradigm shift.

Introduction

As a way of finding a solution to the exacerbating effects of the Russia-Ukraine war on the already existing food insecurity in Africa, Senegal’s President Macky Sall, who is currently the chairman of the African Union met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in the Russian city of Sochi to discuss the effect on 1.3 billion people in Africa (Yusuf, 2022).

In a similar tone, Africa Development Bank President Akinwumi Adesina literally cried that the Russian blockade of ships in the Black Sea was holding back millions of tons of Ukrainian grain meant for other countries including Africa, and how the rise in oil prices is hurting Africa’s economy (Yusuf, 2022).

Arguably, the literal lamentations from the two officials from Africa explain not only a paradox or an irony of the situation for a continent that according to the United Nations is home to about 30 percent of the world’s mineral reserves, 12 percent of the world’s oil and 8 percent of the world’s natural gas reserves (Al Jazeera Staff, 2022). Undeniably, these resources range from agriculture to fossil fuels and solid minerals.

On the flip side of the same coin, the visitation of the chairman of the African Union to the Russian President is not a viable solution to food insecurity facing the African continent. What will the situation of food insecurity in Africa be should the war take a different trend, and dynamics or continue for a longer period of time? What will happen to Africa if the war degenerates into World War III?

Will it not deepen hunger and starvation in Africa? The solution lies in the hands of the continent’s leadership. In other words, the ongoing war must provide Africa with a window opportunity to influence a paradigm shift, especially in the ideological assumption of Africa’s dependency syndrome.

In light of the foregoing, this brief article seeks to draw the attention of African leaders and by extension, African Union to take lessons from the Russia-Ukraine war.

Structurally, the paper is explored from four related segments. The first provides a conceptual analysis of a paradigm shift. The second segment provides a succinct review of food insecurity in Africa. It also examines food insecurity in Africa prior to Russia-Ukraine War. The third segment focuses on two thematic issues.

First, it assesses Africa’s response to food insecurity prior to Russia-Ukraine War. Particularly, it looks at policy program initiatives and dependency syndrome as strategies to tackle food insecurity. And second, the paradox of Africa’s dependency syndrome. The fourth segment proffers the lessons that could influence a paradigm shift in Africa and finally concludes the paper.

Materials and Methods

In order to explore and provides deeper insights into the problem of food insecurity in Africa exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine war, this paper adopted a qualitative approach. Precisely, the paper employs content analysis based on a review of existing secondary sources on the implications of the Russia-Ukraine war in Africa. The reviewed sources included policy documents, scholarly publications, and opinion pieces, such as newspaper articles from the internet through the Google Scholar Search Engine and Bielefeld Academic Search Engine. The aim of selecting content analysis is to help the researcher make inferences from the meaning and relationship of concepts or texts analyzed.

Conceptual Analysis of a Paradigm Shift

Coined by the American physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn in his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) characterized a paradigm shift as a revolution that challenges and ultimately takes the place of a prevailing scientific framework. These challenges arise when the dominant paradigm, under which normally accepted science operates, is found to be incompatible or insufficient with new data or findings, facilitating the adoption of a revised or completely new theory or paradigm (Kuhn, 1962).

Since its inception, it has attracted the attention of scholars which obliges this paper to mention a few if not all.

In the words of Hayes (2022), a paradigm shift connotes a major change in how people think and get things done that overturns and replaces a prior paradigm. In other words, it is safe to agree with Hayes that a paradigm shift provides a window opportunity that challenge existing assumptions struggling to flow or conform to the current prevailing realities. In paraphrase, Hayes (2022) argues that as a concept, a paradigm shift can result after the accretion of irregularities or evidence that challenges the status quo, or due to some revolutionary innovation or discovery.

In a similar connotation, Lombrozo (2016) theorized the concept as “an important change that happens when the usual way of thinking about or doing something is replaced by a new and different way.” Arguably, Lombrozo implies a change of ideas or perspectives believed to be obsolete.

Finally, Purcell (2021) opined that a paradigm shift occurs whenever there’s a significant change in the way an individual or a group perceives something, and the old paradigm is replaced by a new way of thinking, or a new belief. The question that arouses from Purcell’s conceptualization is what is the “old paradigm” that needs replacement?

In the opinion of this paper, the answer suggests ideas translated into policies, programs, practices, procedures, etc. that no longer resonate with the flow of the current prevailing changes or realities. To put it in another expression, a policy, program, procedure, or idea that was once useful is fading out or has faded.

From a theoretical perspective, it makes to mistake to think of a paradigm shift as a theory or group of ideas about how something should be done, made, or thought about.

From the above conceptual analysis or clarifications, it is safe to make the inference that a paradigm shift is a solution-oriented approach that clearly resonates with scientific research programs in both academic and business environments. It is no more confined to industrious, corporate, or business environments considered the traditional setting. It has found its way into politics and development studies.

Applicable to politics, Konvitz (2020) argues about the imperative need for a paradigm shift. He posits that once or twice in a century, a major crisis provokes a paradigm shift, a transformation of the overarching set of rules and assumptions that govern economic and social systems. This becomes imperative when solutions that worked in the past are no longer effective, and when new problems threaten to overwhelm social and political institutions.

A succinct Review of Food Insecurity in Africa

To begin with, it is somehow imperative to understand what food insecurity is. According to Tara O’Neill Hayes, former Director of Human Welfare Policy at the American Action Forum, “food insecurity is not only defined by having insufficient amounts of food, but also by a diet that is lacking in quality, variety, or desirability” (Hayes, 2021).

In the opinion of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), food insecurity is defined as when people lack regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and active and healthy life.

In Africa’s context, the two definitions are reminiscent and applicable. According to fresh data published by the World Economic Forum 278 million people in Africa suffer from chronic hunger which is equated to food insecurity (Armstrong, 2022). This corresponds to 20 percent of the continent’s population. By comparison, ten percent are affected when looked at globally.

Another finding from a recent U.N. assessment estimates that 346 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa face severe food insecurity, meaning one-quarter of the population does not have enough to eat (Schlein, 2022).

According to Welthungerhilfe (2021), the main drivers of food insecurity include wars, climate change, and the Covid-19 pandemic. Added to drivers is the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war.

Given the subsidence of the Covid-19 pandemic, it can be argued that the virus seems not to be a potential driver of food insecurity in Africa. Understandably, the effects of the numerous civil wars that Africa is still struggling to tackle remain a potential driver. Factually, the wars have grossly affected the agriculture industry in Africa.

Agricultural production is the key to the region’s economy because on average, 15% of the GDP comes from and two-thirds of the population employed in the agricultural sector in Africa. Particularly in East and Central Africa, Somalia, agricultural production has been thwarted by prolonged conflict and political instability. Due to the stagnant improvement in agricultural productivity, food insecurity is prevalent in rural areas in Africa (NEPAD, 2013).

Climate change which is arguably natural but sometimes influenced by human actions remains a potential driver as well. In the opinion of this paper, the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war is a new phenomenon that should not have been among the drivers. In the subsequent segment of this paper, this is discussed in detail.

Food Insecurity in Africa Prior to Russia-Ukraine War

Premised on the fact that the Russia-Ukraine war has worsened or exacerbated food insecurity in Africa, it simply suggests that food insecurity has been a problem in Africa before the conflict that started on 24 February 2022. Below provides some pieces of evidence to substantiate the claim.

According to the head of the African Development Bank (AfDB) Akinwumi Adesina, “some 283 million people were already suffering from hunger” in Africa (AFD, 2022). To correlate Adesina’s assertion, Debo Akande, Senior Specialist and Head of Agribusiness and Mechanisation at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture asserts ‘Before the war in Ukraine, most countries in Africa were already grappling with soaring food prices due to extreme climate, terrorism-induced instability and the Covid-19 pandemic, which disrupted production efforts and global supply chains,’ ‘Since Russia’s invasion, global food prices have reached new highs with Africa badly hit” (Oluigbo, 2022). The only difference is the lack of statistical evidence in Akande’s claims.

In addition, research reveals that about 21% of people on the continent suffered from hunger in 2020, a total of 282 million people. Between 2019 and 2020, in the aftermath of the pandemic, 46 million people became hungry in Africa. No other region in the world presents a higher share of its population suffering from food insecurity than Africa (Fuentes-Nieva, 2022).

The Food and Agriculture Organization also reported that in 2021, hunger affected 278 million people in Africa, and while most of the world’s undernourished people live in Asia, Africa is the region where the prevalence is highest (FAO, n.d.).

Finally, Lena Simet, senior researcher on poverty and inequality at Human Rights Watch asserted “Many countries in Africa were already in a food crisis,” “Rising prices are compounding the plight of millions of people thrown into poverty by the Covid-19 pandemic, requiring urgent action by governments and the international community.” (Human Rights Watch, 2022).

Owing to the argument that statistics is not an exact science, it could be used as a crutch to question the accuracy or veracity of the quantitative evidence of food insecurity in Africa. However, any counter-argument will not deny or erase the reality of the prevalence of food insecurity in Africa before the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Africa’s Response to Food Insecurity prior to Russia-Ukraine War

Premised on the fact established by this paper that food insecurity has been a problem in Africa before the Russia-Ukraine war, the question that pleads for a sincere answer is what has been Africa’s response to food insecurity? Or what has Africa been doing? At the continental level, the response is twofold. The first is through policy program initiatives and the second is through dependency syndrome. Let’s examine the twofold beginning with program initiatives.

Deeply concerned about the far-reaching impacts of food insecurity will have on the continent, In 2003, the Heads of state of the African Union during its Second Ordinary Assembly held in Maputo Mozambique approved an ambitious initiative framed as the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP).

The program, part of the New Partnership for Africa Development (NEPAD), was endorsed as a framework meant to create ambitious institutional and policy transformation meant to boost agricultural productivity on the continent through increased public investment (Songwe, 2012). To put it better in another war, the CAADP considered the Maputo Declaration was inaugurated as the vehicle to stimulate production and bring about food security among the populations of the African continent.

The CAADP offers African countries a clear set of principles, best practices, and thematic policy guidance, as well as targets by which they can align their individual agricultural strategies and plans to fit local realities and capacities.

The explicit goal of CAADP was to “eliminate hunger and reduce poverty through agriculture” In pursuit of this aim, African governments commit to two “targets.” The first is to achieve a 6 % annual growth in agricultural productivity by 2015. The second was to through commitment increase the allocation of national budgets directed to the agricultural sector to at least 10 percent (CAADP, 2011), (Sasson, 2012).

It has been a little over a decade since the endorsement of the CAADP. Did it achieve the desired goals or objectives? To make any conclusion, let’s briefly assess the impacts.

In 2012, 40 African countries have engaged the CAADP process, some 30 signed CAADP compacts, and 23 finalized investment plans. Moreover, according to the head of CAADP in New Partnership for Africa Development (NEPAD), Martin Bwalya, “about 9 to 15 countries have had very significant financing of their investment plans” (Bwalya, 2012).

Unarguably, it can be inferred that the worsening of food insecurity due to the effects of the Russia-Ukraine War suggests that the CAADP did not impact the continent as envisaged after a decade. The recent policy engagement between the Wilson Center Africa Program and the Environmental Change and Security Program, in partnership with the United States Department of State and the for Agriculture, Rural Development, Blue Economy, and Sustainable Environment that focused on “Africa’s Policy Priorities for Food Security and Nutrition” could be used as the evidence to support the claim (Wilson Center, 2022).

During the policy dialogue, H.E. Ambassador Josefa Sacko admitted to the core, systemic challenges of food insecurity and highlighted another five ambitious priority remedies. First: increase food production, especially of staple foods. Second: reduce post-harvest food losses to make more food available and reduce the production carbon footprint.

Third: invest in climate-smart agriculture to produce climate-smart technology that reaches Africa’s farmers. Fourth: promote inter-African trade in agriculture and services via the African Continental Free Trade Area. And fifth: Strengthen mutual accountability through the CAADP annual review mechanism to take stock of progress and pinpoint areas of focus for member states in agricultural transformation (Wilson Center, 2022).

Supportive to the above claim that the CAADP did not impact the continent as envisaged, Amb. Sacko also announced that AU is working to establish an African Food Safety Agency, which, according to her is an initiative that would allow the AU to welcome collaboration with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Wilson Center, 2022).

Dependency Syndrome

This paper opinionates that Africa has been responding to food insecurity through dependency syndrome. According to Phil Bartle, “dependency syndrome” is an attitude and belief that a group can not solve its own problems without outside help. It is a weakness that is made worse by charity (Bartle, 2012). Similarly, The Safari Mission website defines dependency syndrome “as when people look to others to be their source, avoiding personal responsibility by putting the responsibility for their life on other people”.

Safari Mission argues that dependency syndrome has become a huge issue in many places around the world, particularly in poorer areas where well-meaning and good-hearted people have come to help the situation by providing for the needs of the poor (Admin, 2020).

Arguably, most African countries have been recipients of foreign assistance or aid since their independence. It has developed a culture of dependency in Africa and fostered paternalism, instead of a partnership. Before the war, Russia and Ukraine were key sources of food commodities for Africa. North Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia), Nigeria in West Africa, Ethiopia and Sudan in East Africa, and South Africa account for 80 percent of wheat imports from the two countries (Mlaba, 2022; One Africa, 2022).

As corroborative evidence, WITS (2022) opined that the majority of African countries were heavily dependent on food imports, especially wheat, from Russia and Ukraine to meet the demand of domestic markets. For instance, both Benin and Somalia obtained all of their wheat from Ukraine and Russia In 2019 and 2020, the dependency of Egypt, Sudan, Kongo, Senegal, and Tanzania on Russian and Ukrainian wheat imports stood at 82%, 75%, 69%, 66%, and 64%, respectively (Hatab, 2022).

Moreover, Kenya purchased over 30 % of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine in 2021, for instance, the manufacture of bread in Kenya, which is the third most eaten food item in that country, would be impacted if there was a disruption in the supply chain Sen (2022).

In the year 2021, Russia accounted for 44 % of Cameroon’s total imports of fertilizers (Sen 2022). Consequently, Ben Hassen and El Bilali (2022) argued that because the war between Russia and Ukraine involves two major agricultural powers, it has a variety of negative socioeconomic implications that are now being felt internationally in which Africa is the most affected continent and that could get significantly worse as long as the war continues, particularly for global food security.

In passing, it would be wise to similarly mention that African markets have become heavily dependent on rice importation, especially from Asia. Take a look at a few instances. More than two-thirds of rice consumed in Liberia is imported from abroad, particularly India, China, Myanmar, Thailand, Pakistan, etc. (EIB, 2022). Moreover, to meet the high demand for rice, Liberia imports nearly 300,000 metric tons annually, costing an estimated US$ 200 million (CGIAR, 2020). In 2021, Sierra Leone spent over $240 million annually on the importation of rice (Thomas, 2021).

In Guinea, rice is the largest imported food item, making up almost 40 % of all food imports and accounting for 690 thousand tons in 2020 and over USD 200 million annually. The second largest item is wheat flour (Guinea-Country Commercial Guide, 2021). Nigeria relies on $10 billion of imports to meet its food and agricultural production shortfalls (mostly wheat, rice, poultry, fish, food services, and consumer-oriented foods) (Nigeria-Country Commercial Guide, 2021). According to the Senegal National Agency of Statistics and Demography, Senegal imports up to 80% of its rice needs.

Average per capita rice consumption is trending up, now estimated at 91 kg per year. Indian broken rice is most prevalent in the market. According to Trade Data Monitor, India was the top rice supplier to Senegal in the market year 2021/22, with a 55 percent market share, followed by Thailand (22 percent), Brazil (12 percent), and China (4 percent). About 98 % of Senegal’s rice imports are broken rice (Bousso, 2022).

The Paradox of Africa’s Dependency Syndrome

Unarguably, it sounds paradoxical for Sub-Saharan Africa so blessed with abundant natural resources, fertile soils, and beautiful weather to employ dependency syndrome as a strategy to tackle food insecurity. From a globalization perspective that encapsulates international trade, it can be argued that no nation can easily claim self-sufficiency in food. However, it cannot possibly justify Africa’s dependency syndrome.

This is simply because Africa’s geographical advantage favors agriculture that attracts foreign visitors that often marvel at the unexpected. For the first time, the Rothamsted Research, World Agroforestry, and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture research findings reveal that Africa becomes the first continent to chart soil fertility in every single field.

The study established Soil map ‘more detailed than Europe’s could boost livelihoods and human health across 54 nations. According to the findings, from the Tunisian coast, all the way to the Cape some 5,000 miles away the iSDAsoil map charts the continent’s 3.4 million square miles of potential agricultural land in unrivaled detail at roughly 24 billion locations. It means that for every single field on the continent, vital information such as the acidity, organic content, and nutrient levels of the soil is now available. This can help advise farmers in a number of different areas, such as yield forecasting, crop suitability, and fertilizer application (Rothamsted Research, 2020).

Interestingly, Africa has 24% of the world’s agricultural land, and 17% of the arable. So why then Africa is the hungriest continent in the world and a net food importer? Africa imports a third of the cereals it consumes, and 64% of the wheat, according to the analysis based on data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. By comparison, Ukraine which has just 14% of Africa’s arable land was, before the current conflict, able to feed the continent (Kamande, 2022).

With this huge and undisputable potential, should Macky Sall, the current chairman of the African Union literally cry to Russian President Vladimir Putin about the effect of the war on 1.3 billion people in Africa (Yusuf, 2022)? What a crystal-clear paradox for Africa!

The Lessons for a Paradigm Shift in Africa

Unquestionably, the exacerbating effects of the Russia-Ukraine war on the already existing food insecurity in Africa warrant an imperative need for a paradigm shift in response to food insecurity. Africa must see the effects of the current Russia-Ukraine war as a window opportunity to reduce its reliance on food imports from outside the Continent. Of course, constructive engagement through dialogue with Vladimir Putin to stop the war is encouraging because it will save the precious lives of innocent civilians but does not seem to proffer a long-term solution to the challenge of food insecurity in Africa from 2007 to 2022. Moreover, constructive engagement will not shift the paradigm.

In theory, all of the policies or program initiatives mentioned in this paper are good and workable for building resilience for food security but require sustained political commitment or political will from African leaders.

This is because Africa’s continuance reliance put the continent at serious risk especially the proclivity for political instability due to food insecurity. The case of the most recent popular uprising that led to the demise of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa of Sri Lanka, who fled his country after months of sustained protests blaming him for the country’s economic collapse and widespread hardship could be viewed as another lesson for the continent of Africa leadership (Schmall, Gunasekara,& Mashal, 2022). Despite the government citing the global economic consequences caused by the Russia-Ukraine War as part of its justifications, the citizens did not welcome the excuse or idea. The hardship defied the citizens’ limit of tolerance against the government.

In the context of Africa, it is worth asking these questions; what becomes the plight of the continent regarding food insecurity should the Russia-Ukraine conflict continues? What could happen if China, one of Africa’s biggest rice suppliers invades Taiwan? What could also happen if other major rice suppliers to Africa are in crisis? While it is true that war is not being prayed for, the same is also true that because of the dynamics in the trends of the international order affecting globalization, the possibilities for conflict as in the Russia-Ukraine war cannot be ignored or ruled out.

It is shocking to know how the Russia-Ukraine war has exposed the weaknesses of several political and economic structures in Africa, and the most severe direct impacts of the conflict are on the region’s food and fuel insecurity and internal conflict patterns. Several African countries are experiencing internal conflict manifested by protests due to a hike in food and petroleum products prices. Moreover, national currencies are heavily depreciating against the United States dollar. Below are a few examples.

Consumer inflation topped 37% in Ghana in September while the cedi currency has lost more than 40% of its value as of 6 November 2022. This situation has created serious economic hardship that prompted a series of protests and outcries demanding the resignation of resident Nana Akufo-Addo (Aljazeera, 2022). Sierra Leone is also got its fair share. This is evidenced by the most recent protest in which about 21 protesters and six officers were killed due to frustration over the soaring cost of living spins out of control(The Guardian, 2022).

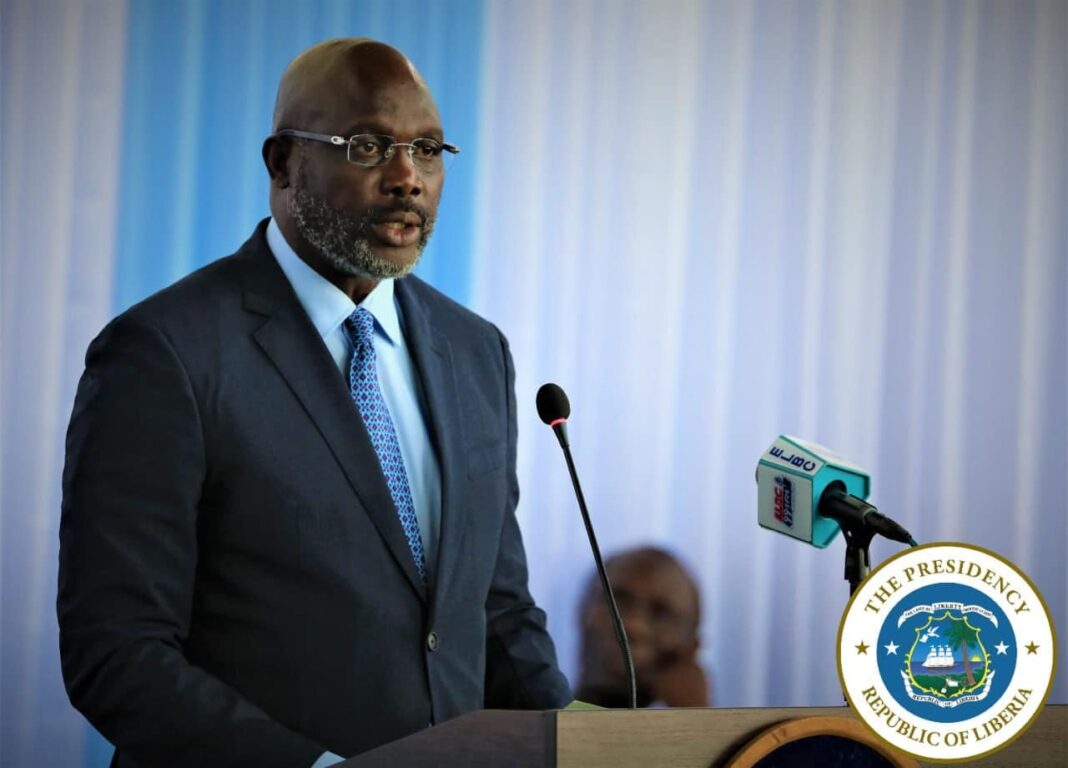

Liberia is also no exception. Judging from the history of rice as a political commodity, it is easy to infer that protest looms over Liberia due to the current and prolonged shortage of rice, the nation’s staple food. It is no secret that several Liberians and political pressure groups threatened mass rallies and protest action against the government if President George M. Weah failed to tackle the current rice crisis in Liberia (Peters, 2022).

Somalia seems to be the worst-case scenario. Nearly all the wheat sold in Somalia is imported from Ukraine and Russia. Should the crisis continues, what will the future hold for the people of Somalia (Faruk & Larson, 2022)?

In Cameroon, where more than half of the population was food insecure before the war, the cost of imported food is driving local food inflation, with bread and other staple foods increasingly out of reach to those with low incomes. In Kenya, where nearly 7 out of 10 people were food insecure before the war but only 1 out of 10 are covered by at least one form of social protection, the cost of cooking oil increased by 6.5% between February and March alone. In Nigeria, where food insecurity affected nearly 6 out of 10 before the war, year to year food inflation was 17.2% in March, with prices of bread, rice, and yams rising even faster, by more than 30% (Human Rights Watch, 2022).

In general terms, African countries imported 44% of their wheat from Russia and Ukraine between 2018 and 2020, according to U.N. figures. The African Development Bank is already reporting a 45% increase in wheat prices on the continent, making everything from couscous in Mauritania to the fried donuts sold in Congo more expensive for customers (Faruk & Larson, 2022).

Interestingly, the affected masses in Africa are refusing to agree with their respective governments shifting the blame to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The reason seems to be very simple. Despite the global economic consequences caused by the Russia-Ukraine War, other governments outside Africa are doing better to curtail or minimize the effects. Through its embassy in Ghana, Russia politically reacted that the hikes in food prices and fuel products on the African continent were not because of Russia’s military action in Ukraine. According to the Embassy, “food and energy prices began to rapidly rise already in early 2020 due to systemic miscalculations of the financial and economic policies of Western countries during the COVID-19 pandemic” (Ankrah, 2022).

Conclusion

Judging from the exacerbating effects of the Russia-Ukraine war on food insecurity, this paper has addressed the imperative need for a paradigm shift in Africa’s response or approaches to addressing food insecurity. The paper has provided the argument for Africa’s leadership to see the negative impacts of the war as a lesson to learn from. In other words, the exacerbating effects of the Russia-Ukraine war on food security in Africa, speak clear volumes for a paradigm shift.

While it is arguable that from a globalization perspective, nations are interdependent, however, it does not necessarily mean dependency syndrome as shown by Africa. For instance, or as a reminder, Africa has 24% of the world’s agricultural land, and 17% of the arable (Kamande, 2022). Therefore, it is about time for the leadership of Africa to make wise use of this geographical advantage.

The paper also concludes that Africa’s continuous reliance on the outside to address food insecurity has implications for political instability. This assertion comes as a prediction justified by the notion that society has its own limit of tolerance to live with conditions that threaten its survivability.

Finally, the paper concludes that Africa’s potential to shift the paradigm lies in sincere and sustained political commitment or political will to change the narrative that is absolutely possible.

References

Ankrah, A. (2022) Ghana: Don’t Blame Russia for Hike in Food, Fuel Prices – Embassy

https://allafrica.com/stories/202207070176.html

Admin (2020) The Dependency Syndrome | A Fork in the Road 1

https://safarimission.org/articles/the-dependency-syndrome-a-fork-in-the-road-1/

AlJazeera Staff (2022) Mapping Africa’s natural resources

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/2/20/mapping-africas-natural-resources

Aljazeera (2022) Ghana protesters say Akufo-Addo ‘must go’ as inflation Worsens

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/11/6/protesters-in-ghana-call-

for-presidents-resignation

AFD (2022) Ukrainian War Worsens African Food Crisis

https://www.afd.fr/en/actualites/ukrainian-war-worsens-african-food-crisis

Bartle, P. (2012) The Dependency Syndrome

https://cec.vcn.bc.ca/cmp/modules/pd-dep.htm

Bousso, M. (2022) Grain and Feed Annual

Bwalya, M. (2012) Martin Bwalya on CAADP progress. Institutional reforms vital for sustaining achievements. Johannesburg

http://www.donorplatform.org/caadp/interviews/671-martin-bwalya-on-caadp-progress.html

Ben, T., & El Bilali, H. (2022). Impacts of the Russia-Ukraine War on Global

Food Security: Towards More Sustainable and Resilient Food Systems. Foods, 11(15), 2301.

CAADP (2011). “Countries with Compacts/Investment Plans Status Update.” November 2011. CAADP: Midrand, South Africa.

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/2/20/mapping-africas-natural-resources

CGIAR (2020) Africa Rice and Liberia solidify ties to build resilient rice-based food systems

https://www.cgiar.org/news-events/news/africarice-and-liberia-solidify-ties-to-build-resilient-rice-based-food-systems/

European Investment Bank (2022) Liberia: EIB to support Increase in rice production

https://www.eib.org/en/press/all/2022-264-eib-to-support-increased-rice-production-in-liberia

Falck-Zepeda, Benjamin J., Gruère, G. & Sithole-Niang, I (2013) Genetically

modified crops in Africa. Economic and policy lessons from countries south of the Sahara. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/genetically-modified-crops-africa.

Faruk, O., & Larson, K.(2022) War in Ukraine adds to food price hikes, hunger in Africa

https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-moscow-black-sea-5fbafb9ea7403a5071f696f66c390180

Fuentes-Nieva, R. (2022) Growing hunger, high food prices in Africa don’t have to become worse tragedy

https://newint.org/features/2022/06/07/ukraine-war-has-hit-africa-food-security

FAO (n.d.) Food security indicators – latest updates and progress

https://www.fao.org/3/cc0639en/online/sofi-2022/food-security-nutrition-indicators.html

Guinea-Country Commercial Guide (2021) Guinea – Agriculture Sector – International Trade Administration

https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/guinea-agriculture-sector

Hayes, A. (2022) What Is a Paradigm Shift? Definition, Example, and Meaning https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/paradigm-shift.asp

Hayes, T. O. (2021) Food Insecurity and Food Insufficiency: Assessing Causes and Historical Trends

Human Rights Watch (2022) Ukraine/Russia: As War Continues, Africa Food Crisis Looms

https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/28/ukraine/russia-war-continues-africa-food-crisis-looms

Hatab, A. A. (2022) Africa’s Food Security under the Shadow of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict

https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1691173/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Kuhn, T. S. (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions International

Encyclopedia Of Unified Science https://www.lri.fr/~mbl/Stanford/CS477/papers/Kuhn-SSR-2ndEd.pdf

Konvitz, J. (2020) Paradigm shifts

https://www.fondapol.org/en/study/joseph-konivtz-paradigm-shifts/

Kamande, A. (2022) Africa is so rich in farmland – so why is it still hungry?

https://views-voices.oxfam.org.uk/2022/07/africa-is-so-rich-in-farmland-so-why-is-it-still-hungry/

Lombrozo, T. (2016) What Is A Paradigm Shift, Anyway?

https://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2016/07/18/486487713/what-is-a-paradigm-shift-anyway

Mlaba, K. (2022). How Will the Ukraine-Russia War Impact Africa? Here’s What

to Know. Global Citizen, 02 March 2022 https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/ukraine- russia-war-impact-africa-hunger-poverty/

Nigeria-Country Commercial Guide (2021) Nigeria – Agriculture Sector –

International Trade Administration. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/nigeria-agriculture-sector

Oluigbo, U. A. (2022) The war in Ukraine has hit Africa’s food security

https://newint.org/features/2022/06/07/ukraine-war-has-hit-africa-food-security

One Africa. (2022). Ukraine, and the New Geopolitics / IPI Global Observatory.

https://theglobalobservatory.org/2022/03/africa-ukraine-and-the-new-geopolitics/

Purcell, N. (2021) What is a Paradigm Shift in Business? – Definition & Examples

https://study.com/academy/lesson/what-is-a-paradigm-shift-definition-examples.html

Peters, L. G. (2022) Liberia: Protest Loom Over Rice Shortage

https://allafrica.com/stories/202210050071.html

Rothamsted Research (2020) Africa becomes first continent to chart soil fertility in every single field

https://www.rothamsted.ac.uk/news/africa-becomes-first-continent-chart-soil-fertility-every-single-field

Schlein, L. (2022) Sub-Saharan Africa Facing Severe Food Shortage

https://www.voanews.com/a/sub-saharan-africa-facing-severe-food-shortage/6655559.html

Sasson, A. (2012) Food security for Africa: an urgent global challenge

https://agricultureandfoodsecurity.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2048-7010-1-2

Songwe, V. (2012) Strategies to Improve Food Security In Africa

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/01_food_security_songwe.pdf

Sen, A, K. (2022) Russia’s War in Ukraine Is Taking a Toll on Africa.

https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/06/russias-war-ukraine-taking-toll-africa

Schmall, E., Gunasekara, S. & Mashal, M. (2022) Sri Lanka’s President Resigns After Months of Protest

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/14/world/asia/sri-lanka-president-rajapaksa-resigns-protests.html

Thomas, A. R. (2021) Sierra Leone continues to spend over $240 million annually on import of rice – says trade minister

https://www.thesierraleonetelegraph.com/sierra-leone-continues-to-spend-over-240-million-annually-on-import-of-rice-says-trade-minister/

The Guardian, (2022) ‘Explosion of violence’: Sierra Leone picks up the pieces after protests

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/aug/21/sierra-leone-protests-inflation-cost-of-living

Wilson Center (2022) Africa’s Policy Priorities for Food Security and Nutrition

https://www.wilsoncenter.org/event/africa-food-security-nutrition

World Integrated Trade Solution Database (2022) “Trade Stats.” WITS: World

Bank. https://wits.worldbank.org/

Yusuf, M. (2022) African Union Chair Meets Putin to Discuss Food Insecurity

https://www.voanews.com/a/african-union-chair-meets-putin-to-discuss-food-insecurity/6602093.html