By Mark B. Newa

GANTA, NIMBA COUNTY – On one sunny day in Karnwee late last year, forest rangers and police officers seized a truck with 80 pieces of boxlike timber, ending an hourlong chase all the way from Bahn, where the woods had been harvested.

Emmanuel Gongor, a middle-height man, arrived on the scene shortly on a motorcycle taxi, appearing shocked. This was not the first time Gongor had transported block wood, commonly called “Kpokolo” in the logging industry. For years he passed checkpoints without any problems. Sometimes he sold the wood to other companies or individuals in Liberia. Other times, he exported them.

Things had suddenly changed. Gongor learned that the Forestry Development Authority (FDA) had banned Kpokolo, derived from the sound the wood makes when it falls or “thick and heavy” in the Kpelle language. His woods were dumped by a roadside.

“We have been so committed, but if we cannot understand, we will seek the legal process by taking the FDA to the circuit court,” a furious Gongor told The DayLight in a phone interview days after the incident. He expected to get US$7,000 from the consignment and settle all of his holiday expenses.

Gongor does not have a logging contract and his timber surpass the dimension defined in the Chainsaw Milling Regulation. His woods are between five and 10 inches thick, up to five times the required measurement of two inches. In photos posted to Gongor’s Facebook page, several men can be seen trying to lift the timber.

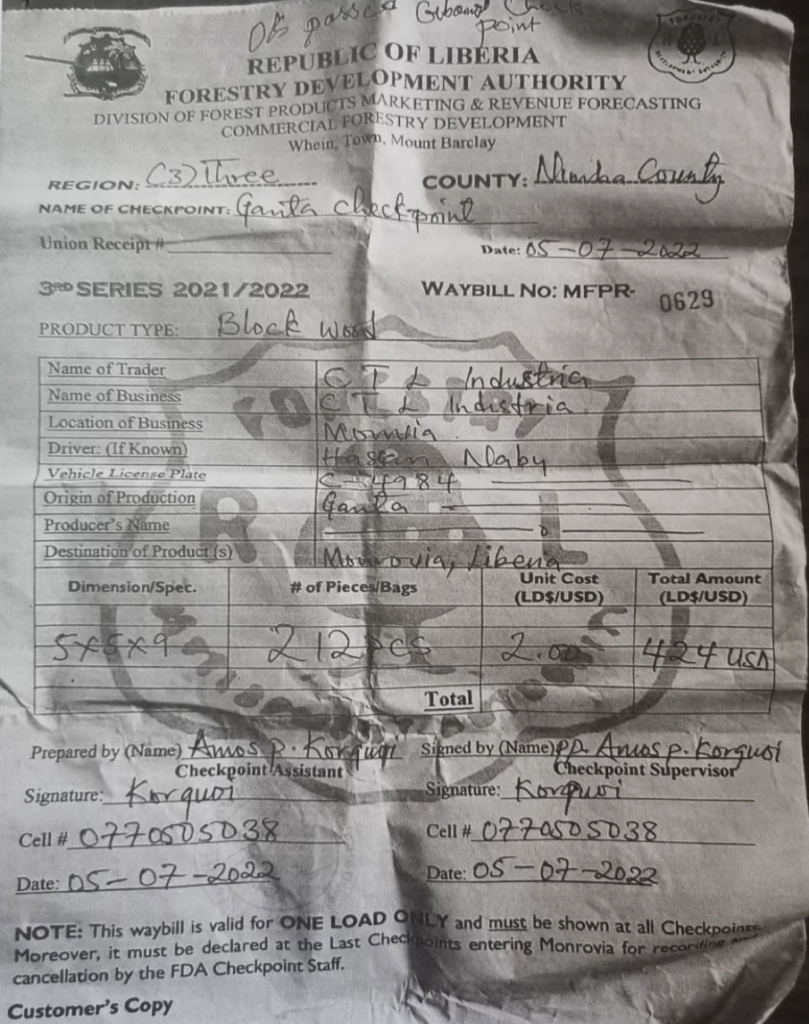

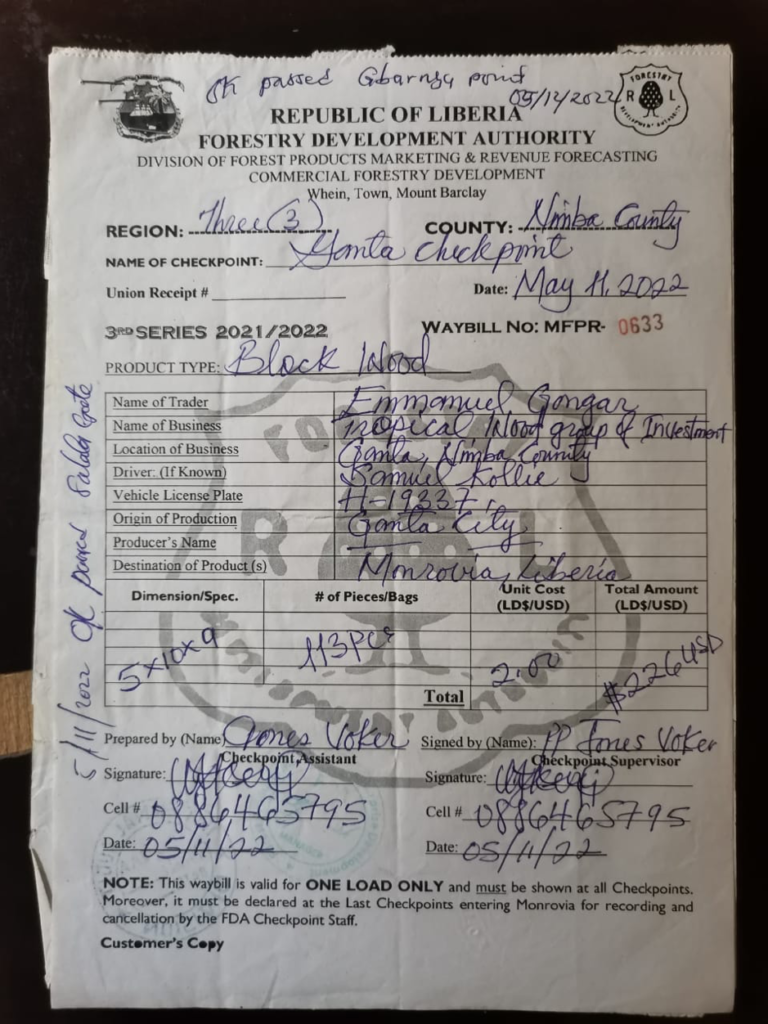

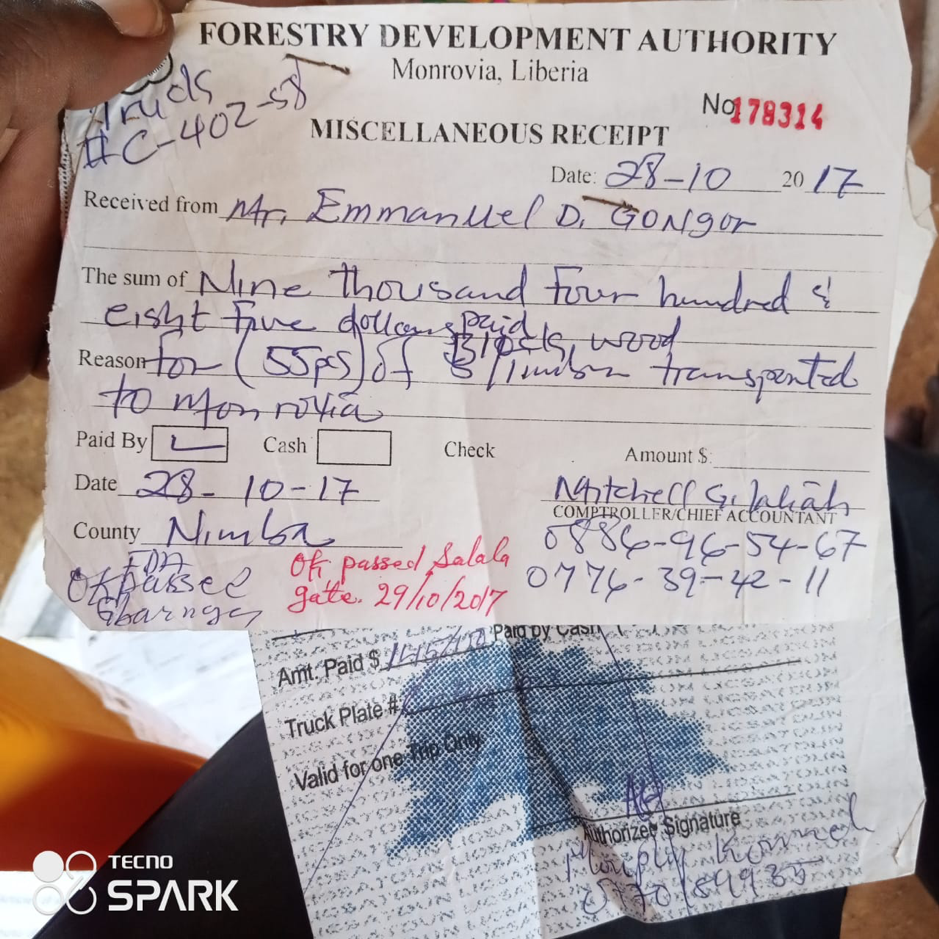

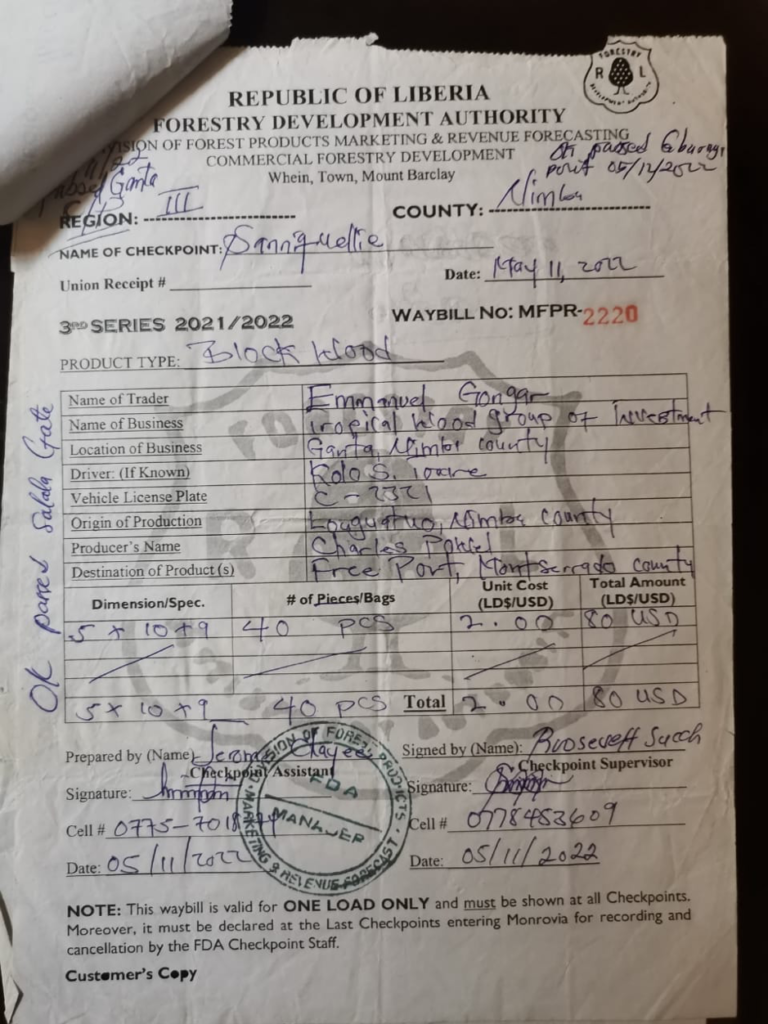

But interviews and documents show that the FDA has been aware of Gongor’s illegal logging activities for half of a decade. In fact, the agency has unlawfully received fees from him. Some of his waybills seen by The DayLight amounted to over US$1,500.

Those payments sanctioned the 48-year-old to rip off forests from central Nimba to the Cote d’Ivoire border. Nimba lost 315,000 hectares of tree cover between 2001 and 2021. That makes it second only to Bong County (363,000 hectares), according to Global Forest Watch, a tool that monitors the state of forests across the world.

‘Emmanuel, The Investor’

Gongor was an accomplished miner. He panned and sieved for gold on a number of goldfields in Gbarpolu, Grand Kru and Grand Gedeh.

He started up in the logging industry in 2017 as a chainsaw miller, pit-sawyers or plank producer. Soon he saw that he could make more money from harvesting kpokolo.

“Block wood is preferable because for normal sawing at times, we take 500 pieces of timber to be a truckload, but for block wood, some are just 150-200 pieces,” Gongor explained. “For the past six years now, I have been on that operation.”

Gongor was hired by a Turkish-owned firm called Tropical Wood Group of Companies, which obtained a one-year permit from the FDA to buy and sell. The permit was issued by Darlington Tuargben, the FDA Managing Director at the time. The legality verification department (LVD), a unit of the FDA that manages its log-tracking system called the chain of custody, said it has no record of the company. Efforts to contact Abdulla Aklan, the company’s owner, were not successful. Tuargben did not respond to queries.

Gongor conquered the kpokolo black market. He broke out with his employer and established Tropical Wood Group of Investment. Though he is yet to register it as a legal entity, he continues his criminal deals with the new firm.

His network spans four of the nine districts in Nimba: Zoe-Gbao, Zoe-Geh, Bu-Yao and Gbelay-Geh in the central and eastern regions of the county. He boasts of a workforce of 25 people and a host of villagers and disadvantaged youth or “zogoes.” They do everything from locating forested communities to finding trees and from negotiating with local landowners, to harvesting, hauling and transporting. With 30 chainsaws, they have built wooden bridges, and town halls and have repaired schools and clinics in forested towns and villages.

Videos recorded by Gongor show him taking stock of trees he had negotiated with villagers to harvest in Tahnplay, and celebrating the completion of projects. “We finally completed the bridge connecting Kanhplay to Sehyi Town in Gbelay-Geh Statutory District,” Gongor can be heard saying in one video. “Together with the youth, elders, and chiefs, we were able to complete the first phase of operation.”

Townspeople in the areas Gongor works revere him. His name goes beyond the reach of logging companies in that region, many of whom have failed to fulfill their social agreements with communities.

“We call him Emmanuel The Investor,”Arkey Vasiee, town chief of Zortapa.

In March last year, James Zuorpeawon, Gbehlay-Geh’s development superintendent, issued him a permit to operate in the area. It authorizes Gongor to present the document “for awareness and protection during his operation within the district.”

Other kpokolo loggers across the country also respect Gongor.

“This place is small for him, he can’t even come here again,” said a plank producer from Gompa Wood Field in Ganta, who preferred not to be named. Gongor had milled planks there prior to venturing into kpokolo.

“Gongor is one of the most skillful kpokolo operators,” said James Kelley, a kpokolo logger in Gbaryama in Gbarpolu’s Bopolu District. Kelley said he had worked with him in Kinjor, Grand Cape Mount County.

Gongor does not depend on his fame—or notoriety—to run his business. He advertises on Facebook. “[If you are] interested in this Iroko table, you can WhatsApp me on this number,” a November 27, 2020 post reads, featuring a flat piece of log on a stick like a table. “If anyone is interested in buying teak wood, just contact me on my contact number,” reads a March 10, 2021 post. Both Iroko and teak logs are durable woods used for outdoor purposes. His accounts also showcase selfie pictures of him with men loading giant-sized block wood onto trucks.

But Gongor would not have been this successful without the FDA. Receipts of their transactions show he has paid the FDA tens of thousands of United States Dollars in waybill, fees imposed on transported timber. One September 2017 receipt shows that he paid the FDA L$18,000 for 300 pieces of kpokolo. Another in May last year reveals he paid US$424 for 121 pieces.

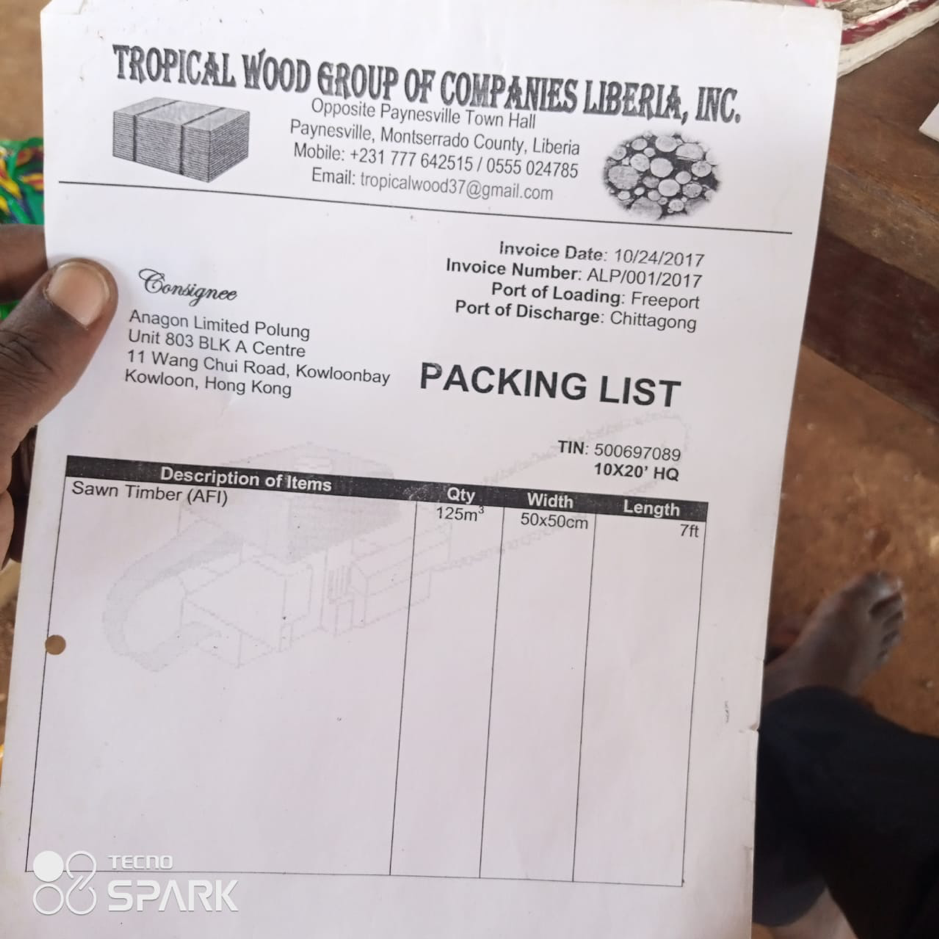

One document shows Gongor’s invoice to a firm in Hong Kong to export 125 cubic meters of sawn timber with a height and width of 50 centimeters (approximately 20 inches) and length of seven feet. He had a deal to export timber from the Freeport of Monrovia to the Port of Chittagong in Bangladesh, according to one invoice.

“The FDA agents are always informed when we are going to bring wood from the bush,” Gongor told The DayLight.

“We make more money for forestry. Our own percentage to the FDA is different from the normal [pit-sawing].” He was speaking in reference to the US$0.60 toll on a plank compared to US$2 on kpokolo, according to waybills FDA issued him, seen by The DayLight.

The fees the FDA received from Gongor are illegal in a number of ways. First, the payments he has made to the FDA do not go to the Liberia Revenue Authority (LRA), the company’s tax-payments record shows. In addition to possessing no contract, the villages where he operates do not have any legal rights to engage in logging deals. And the timber he harvests or exports does not pass through the legal channel, as mandated in the National Forestry Reform Law and the Regulation on Establishing a Chain of Custody System.

Gongor’s kpokolo waybills have also shined a light on FDA’s shady plank tolls system. Fees the agency collects from planks dealers are not made public as required by forestry’s legal frameworks, including Liberia’s Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA) with the European Union. They are neither paid to the LRA nor captured in the reports of the Liberia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (LEITI). The FDA has retained these fees for years, a breach of the financial provision of the reform law.

FrontPage Africa reported in 2020 that the Klay checkpoint in Bomi collected over L$500,000 in just one month. It said that there was a wrangle within the FDA over the management of the funds, adding that the fees went into a mobile money account belonging to Edward Kamara, FDA’s forest product marketing manager. Kamara coordinates fees collected at checkpoints countrywide.

Ironically, while the FDA secretly collects fees from Gongor, it has asked the public to assist it to combat illegal logging activities. The FDA said in a release last November that it had intercepted four container trucks trafficking timber from western Liberia. That statement followed a similar one three months earlier after rangers in Bomi and Gbarpolu arrested three trucks with logs illegally harvested.

Earlier this month, the Monrovia City Court issued an arrest warrant for a former police commander, an ex-envoy and eight people in the Bomi-Gbarpolu incident. The FDA is seeking court orders in the counties to auction the logs, the first such step since the formulation of Regulation on Confiscated Logs, Timber and Timber Products.

‘I am over hurt’

Gongor feels betrayed in all of this, believing he is a victim rather than the villain he actually is. For the last six years, the FDA has sanctioned his operations and accepted his payments like a typical chainsaw miller. He finds nothing wrong with producing Kpokolo.

“It would have been good for the FDA to formally inform those involved in the business before ordering us to stop the harvest and sale of block wood in the country,” Gongor said.

“I am over hurt. We have been issued hundreds of waybills. We always pay a huge sum of money to these guys,” he added.

In December, nearly a month after his consignment of timber was seized, Gongor transported them to Ganta. They were again seized and are being kept at the Gompa Wood Field.

The FDA is yet to take the required legal actions to confiscate Gongor’s timber. Under the confiscated timber regulation, The FDA should petition the circuit court in Sanniquellie to auction the wood. Both Arthur Gweh, the commander of Nimba County police detachment in Bahn, and Emmanuel Gbeh, the FDA ranger who arrested the wood, declined to comment.

By law, Gongor should face a lawsuit for his illicit activities, and if convicted he could pay a fine, serve a prison term, or both. It is a crime for a non-contract holder to harvest timber, punishable under the Penal Code as economic sabotage.

The FDA’s Managing Director Mike Doryen did not respond to emailed queries.

Editor’s Note: This is the first of a two-part report on the operations of an infamous illegal logger, based in Nimba County. It is also a part of a broader series on a criminal logging activity commonly called “Kpokolo.”