By

MONROVIA, LIBERIA — Linda Thomas-Greenfield, ambassador to the United Nations, led the United States delegation to the inauguration of Joseph Nyumah Boakai, the newly elected president of Liberia. The West African nation remains one of the US’ few remaining democratic allies in a region where coups, military juntas and anti-Western sentiment are rising.

“I’m excited. I described it as exhilarating to be back. This is a place where I basically started my career in Africa and sort of rounded it out as ambassador from 2008 to 2012,” Thomas-Greenfield told PassBlue in an interview on Jan. 22, the day of the inauguration.

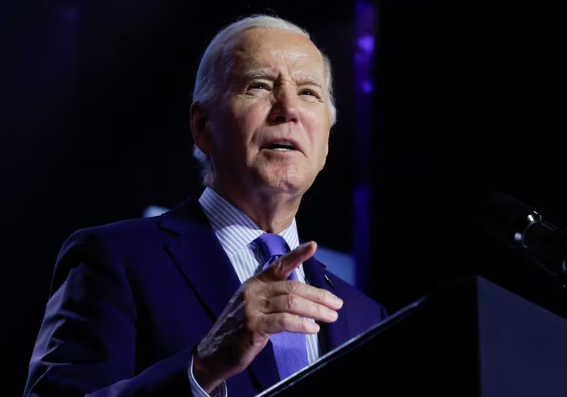

Her trip to Liberia as well as Guinea-Bissau and Sierra Leone, from Jan. 21-26, came amid growing outrage against the US for its vetoing Security Council resolutions calling for a humanitarian ceasefire in Gaza. Approximately, 25,000 Palestinians have been killed in the war since Oct. 7. Thomas-Greenfield’s travel to West Africa also meant she couldn’t attend the French-led ministerial meeting in the Council on Jan. 23, focusing on Gaza. Secretary of State Antony Blinken is also traveling to parts of Africa at the same time.

Last month, on Dec. 19, the outgoing president George Weah reversed Liberia’s vote in the UN General Assembly from a no to yes, in favor of a humanitarian ceasefire. The original Dec. 12 vote by Liberia (a no) will be officially recorded to a yes, the spokesperson of the president of the General Assembly told PassBlue on Jan. 24. The no vote had made Liberia the only country on the continent and one of 10 of the 193 member states to vote against the resolution, including the US and Israel.

In an interview on Liberian radio’s OK Morning Rush show, on Jan. 23, the host’s first question to Thomas-Greenfield was whether the US had pressured Liberia to vote against the resolution.

“Liberia has been a strong partner to us at the United Nations, and most of the time we are in sync and agreement with each other, but there are times when we’re not, and that happens across the board with other countries as well,” she said. “So, there was no pressure on our part. That’s an internal decision that was made by the administration. And we — I don’t have any comment on how that decision was made, but I will say that we hope to continue a strong partnership with Liberia under the new administration at the United Nations.”

On Inauguration Day, Thomas-Greenfield walked down the red carpet in the sweltering West African heat, flanked by suited bodyguards. The UN envoy, who enjoys celebrity status in Monrovia as a former ambassador to Liberia, took a front-row seat, not far from the president-elect in a ceremony attended by the heads of state Sierra Leone and Ghana, Julius Maada Bio and Nana Akufo-Addo, respectively, as well as the prominent South African politician Julius Malema.

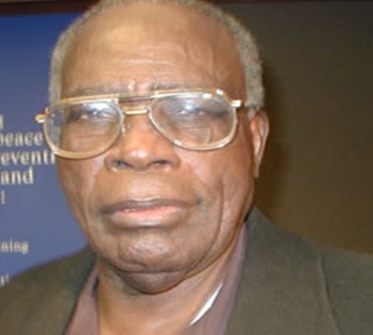

Half an hour into his long speech, Boakai, 79, wearing a traditional African tunic, a medallion necklace and allegedly a bulletproof vest, grew faint. He had to sit down, with his bodyguards shrouding him as he continued to read his speech, while stopping journalists and the audience from filming him. He was soon whisked offstage and later taken home to rest.

Concerns about Boakai’s age and health were raised during the election campaign last year, in which he narrowly won over the incumbent and former soccer star George Weah, by less than one percent of the vote.

Boakai, who had promised to root out corruption and buoy the ailing economy under Weah’s government, outlined his “ARREST” agenda, standing for Agriculture, Roads, Rule of Law, Education, Sanitation and Tourism, in his inauguration speech. It was part of his presidential campaign dubbed “RESCUE,” claiming he would save the state from the difficulties it had faced under the previous government.

“We must discourage the culture of unfinished business, doing things in a haphazard and unserious manner,” Boakai’s speech read. “We must restore hope to ourselves, individually, and as a collectivity. We must also restore dignity and integrity to public service — liveable remuneration and pension schemes to civil servants and foreign service government workers. We must restore respect for the rule of law, and respect for officers of the law across our three branches of government.”

Boakai has said that his government will “set up an office to explore the feasibility for the establishment of a War and Economic Crimes Court (WECC) to provide an opportunity for those who bear the greatest responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity to account for their actions in court.”

Liberia, a coastal nation established by freed slaves from the US, suffered a devastating 14-year civil war that killed 250,000 and displaced two million people and ended in 2003. Thomas-Greenfield was sent as US ambassador two years after Liberia’s first postwar democratic elections, which voted in Africa’s first woman president, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. The issue of prosecutions and accountability had been sidelined by Sirleaf’s government, partly because a Truth and Reconciliation Commission had recommended that she be barred from politics.

Thomas-Greenfield was often considered a strong Sirleaf ally, particularly during the 2011 elections in Liberia, which saw the first woman president win a second term, after the opposition, Congress for Democratic Change, led by Weah (running for vice president), and his presidential running mate, Winston Tubman, boycotted the second round. They claimed election rigging.

Thomas-Greenfield praised Weah for his accepting defeat and the “smooth transition,” from one leader to another. Soon after the elections, the US sanctioned numerous political figures in Weah’s government for corruption and human rights violations, which followed sanctions of key members of his administration in 2022. No one was sanctioned in Sirleaf’s administration, despite many high-level cases of alleged corruption. Many Liberians believe the US determines the outcome of elections and politics in Liberia, and Thomas-Greenfield was asked whether her government took measures to ensure Weah was a “one-term president,” as many of his supporters believe.

“Look, we’re not — we didn’t play a role in the political process here in Liberia. Liberian people voted, and they chose the person of their choice. And it had nothing to do with the decisions that we made on sanctioning people who were engaged in corruption in this — in this country,” she said on the radio program. “It’s up to the administration to determine how they will address these issues moving forward. Again, our sanctions are about breaking laws in the United States. It’s not about holding people accountable in Liberia. That’s for the Liberian people.”

Thomas-Greenfield told PassBlue that she’d seen positive changes in Liberia since she was ambassador, saying: “I think Liberia has changed significantly, going from a country that was in the throes of war, where people were devastated, they were hopeless during that period they didn’t see a future, to a country where people do see opportunity, they do see a future, they feel more empowered than they have ever felt before.

But also, I think there is a lot of expectation, there is a lot of disappointment that they have not achieved more over the years, but still, I find that people remain committed to this country just as I am.”

Thomas-Greenfield’s Liberia visit followed a trip to Guinea-Bissau, to help “shore up its democracy,” and is followed by a trip to Sierra Leone, an elected member on the UN Security Council.

Would Gaza be on the agenda during her trips to Sierra Leone?

“You know, everything is on the agenda with Sierra Leone because it’s about their role in the Security Council and how we work with them and generally what I do on these visits is talk to countries about what their priorities are, how they intend to approach their priorities, what our priorities are and how we intend to approach working with them on our priorities and see where we can come together on issues,” Thomas-Greenfield said to PassBlue.

Liberia has long been a staunch diplomatic ally of the US and often follows the superpower’s foreign policies. Liberia was among the first group of African states to cut ties with Libya and the regime of Col. Muammar el-Qadaffi, months after the NATO intervention kicked off in 2011.

The no vote cast by Liberia against the Dec. 12 General Assembly resolution came after Weah visited Israel and reported discussions about Liberia establishing an embassy in the country to increase bilateral ties. Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen described Liberia as “one of Israel’s biggest friends in Africa.”

During the 1970s, President William Tolbert, who was also head of the Organization of African Unity, the predecessor to the African Union, severed diplomatic ties with Israel and called for Israel’s withdrawal from Palestinian and Arab territories in the aftermath of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. His stance toward Israel represented a rupture from the 27-year rule of William Tubman, who had backed Israel. Some Liberians believe that Tolbert’s stance on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was the reason he was assassinated.

At a ball on inauguration night, attended by members of the Liberian diaspora and local members of the business community, Thomas-Greenfield gave a keynote speech. A cake with Bokai’s picture on it sat uncut a distance away. It was a party that Bokai and his vice president Jeremiah Koung did not attend.

“Liberia’s peaceful transition is especially important given the democratic backsliding we have seen across West Africa,” Thomas-Greenfield said. “Throughout the Sahel, coups have denied citizens the right to dictate their own futures. And leaders have consolidated power and isolated themselves from the international community, often with dire, dire consequences. It is devastating, and it’s frustrating, because just as withdrawing from multilateral institutions can lead to violence and instability, investing in them can lead to safety and progress,” she said alluding to the withdrawal of peacekeepers in Mali.

Thomas-Greenfield playfully chastised the audience for speaking while she was rereading her speech.

“I have faith in this country,” she said. “I have the ultimate faith that this country is up to the task, and you have the urgent responsibility to continue — to continue to choose democracy over corruption and unity over division — not just on election day, not just on inauguration day, but every single day. That is the new administration’s task, and I think that the new administration is up to the task. I believe that the Liberian people are up to the task.”

“Know that you have an ally in me, and you have an ally in the United States,” Thomas-Greenfield added, before signing off.

Liberians and members of the diplomatic community then sidled up for photos with her. Source: passblue.com