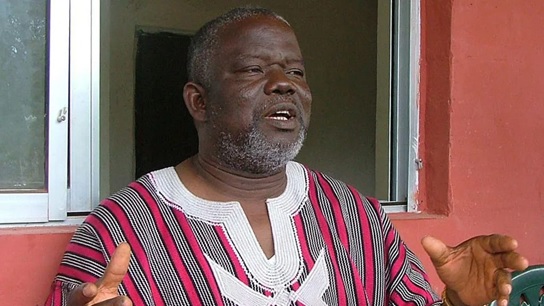

MONROVIA – Prince Yormie Johnson, the former Liberian warlord-turned-politician, passed away on November 28, 2024, at the age of 72. Johnson died at the Hope for Women Hospital in Paynesville, Monrovia after reportedly slipping into a coma the night before. His death comes at a pivotal moment for Liberia, particularly in the context of the long-delayed establishment of a War and Economic Crimes Court.

Prince Johnson rose to global infamy during Liberia’s brutal civil war, leading the Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia (INPFL). His actions, including the notorious capture and killing of President Samuel Doe in 1990, remain etched in the nation’s traumatic history. Following the war, Johnson transitioned into politics, serving as a senator for Nimba County and wielding significant influence in Liberia’s post-war governance.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) placed Prince Johnson at the top of its list of most notorious perpetrators. In its 2009 final report, the TRC identified him as “having the highest number of violations ever recorded for individual perpetrators” during Liberia’s civil wars. Johnson was responsible for the capture, torture, and execution of former President Doe, a brutal act that was recorded and broadcast widely on television. He was also alleged to have participated in killings, extortion, massacres, destruction of property, forced recruitment, assault, abduction, torture, forced labor, and rape.

Johnson’s death is a blow to his victims, who have waited more than two decades for justice. It also comes at a time when momentum for accountability in Liberia is growing. The recent appointment of Cllr. Jallah Barbu as Executive Director of the Office of the War and Economic Crimes Court represents tangible progress toward establishing Liberia’s first mechanism for addressing past atrocities. However, Johnson is now the second faction leader to die without being held accountable, following the 2022 death of Alhaji Kromah, the former leader of the United Liberation Movement of Liberia for Democracy (ULIMO).

Adama Dempster, a Liberian human rights advocate, expressed regret that Johnson was unable to testify before the proposed tribunal. “It’s sad and has a deep meaning for an accountability process,” Dempster told BBC. For many seeking justice, Johnson’s testimony could have been pivotal in uncovering the truth behind Liberia’s darkest days and bringing closure to countless victims and their families.

While many reflect on Johnson’s death, others have not held back their disdain for his legacy. Roosevelt Sackor, a Liberian citizen, echoed similar sentiments on his Facebook page, stating:

“To my government that I elected, please do not give Prince Johnson a state burial because he was the one that killed my father in Caldwell, and my father’s body was eaten by dogs. I am not happy with the way he died because I was waiting for the opening of the war crime court so he could tell me what my father did.”

Such responses illustrate the continuing pain and anger felt by many Liberians who were directly affected by Johnson’s actions. The emotional weight of Sackor’s words emphasizes the deep wounds that still persist, highlighting the demand for justice and accountability that remains unmet for so many families.

Some Liberians, like Austin M. Kawah, a Liberian journalist have begun posting negative responses to Johnson’s death, with Kawah vowing on his Facebook page to resist any attempt to honor him with a state funeral. He stated:

“His body is not going [to the] Capitol Building. He doesn’t deserve a ‘State Funeral.’ We will rally the students’ community and the public to resist and disrupt any attempt by the government to give PYJ a ‘State Funeral.’ His body will be prevented from entering the grounds of the Legislature, and the National Flag will not be laid on his casket… no way.”

Despite these emotional reactions, significant obstacles remain for Liberia in its pursuit of justice. Liberia’s political scene is deeply fragmented, and many former warlords or their allies still hold influential positions in government and society. These individuals, like Johnson, fear that the establishment of such a court could lead to their prosecution.

The death of Johnson stresses the urgent need for Liberia and the international community to dedicate sufficient resources and expertise to establish the War and Economic Crimes Court. As time passes, victims, witnesses, and perpetrators age, diminishing the chances of achieving meaningful justice. The death of Johnson should serve as a catalyst to accelerate efforts to operationalize the court. Perpetrators must be held accountable, and victims must be heard before it is too late.

Prince Johnson’s death results the end of an era for one of Liberia’s most opposing figures. It presents a moment for reflection on the country’s post-war journey and the unresolved issues of justice and accountability. Whether this moment becomes a turning point depends on the actions of Liberia’s leaders and the international community. The call for a War and Economic Crimes Court has grown louder in recent years, and Johnson’s passing removes a key opponent. The question now is whether Liberia will seize this opportunity to confront its past or continue to allow impunity to overshadow justice.