Official documents show that Israel systematically bribed top officials of the murderous dictatorship in Liberia in order to obtain their diplomatic support.

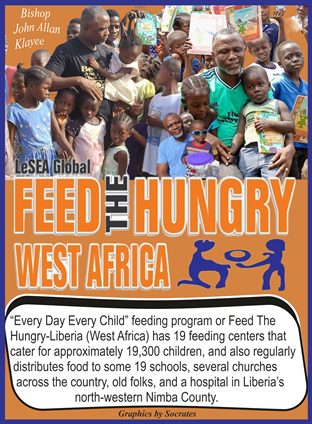

“Honor to the State of Israel!” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu tweeted, referring to the warm welcome he received in Liberia on July 4, 2017. He and Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011, smiled and shook hands warmly. Below the surface, though, tensions simmered. Indeed, the event is comparable to Foreign Minister Shimon Peres’ meeting in 2002 with South African President Nelson Mandela following the demise of the apartheid regime.

Just as Israel had trained and armed the vicious regime in South Africa, which persecuted and imprisoned Mandela and his allies, it emerges that Israel also bribed, armed and trained the dictatorship in Liberia, which persecuted and imprisoned Sirleaf and her opposition colleagues. In the years in which Mandela was targeted by the regime, Peres was in charge of the security ties with South Africa. In the years when Sirleaf was targeted by the regime in her country, Netanyahu was Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations. In return for bribes – in cash, presents and personal benefits – from Israel and assistance to the Liberian regime in carrying out internal suppression, the dictatorship supported Israel, in part through votes in the UN.

This information, which appears in newly declassified Foreign Ministry documents in the State Archives, completely contradicts Israel’s decades-long vigorous public denials. “Israel does not intervene in the internal affairs of any country,” a representative of the Israeli embassy told Liberian journalists in March 1987. “Israel does not supply military aid to Liberia.” The archival documents tell a completely different story. One that does not add to Israel’s honor.

Israel grasped the potential latent in Liberia from the outset. The West African country, which was founded in the mid-19th century by liberated American slaves, was the continent’s first republic. Under the despotic rule of William Tubman, its president from 1944 until his death in 1971, Liberia was one of the few African states that voted in favor of the UN partition plan in November 1947, and recognized Israel in 1948, the year of its establishment. In 1957, Israel opened its first embassy in Africa in Monrovia, the Liberian capital.

“Liberia is one of Israel’s most loyal friends,” Ambassador Pinhas Rodan wrote in a cable to Jerusalem in November 1969. “The country accedes to all our requests in the UN General Assembly and in meetings of the Organization of African Unity.” How was that loyalty achieved? Answer: through systematic bribery and gratuities to Liberian diplomats.

One official who received regular cash bribes was a permanent representative of Liberia on UN committees. “He is a great friend of ours, he makes fiery speeches in our favor,” Ambassador Yeshurun Schiff wrote to his Israeli counterpart in Sierra Leone, requesting his aid in realizing the Liberian representative’s permit to search for diamonds in that country.

The cables show that Israel customarily paid the representative for his support, because he “cooperates to our satisfaction.” Thus, wrote the director of the Foreign Ministry’s Africa Desk in December 1970, “[f]or years we have… been helping him with money and gifts.”

The payments, which were authorized at the highest levels in the Foreign Ministry, came from the official budget. “Grant of $500 approved,” and “additional $500 for small gifts to mark Christmas,” wrote Foreign Ministry deputy director general Avraham Kidron that same December. In another cable he noted that this person “received $1,000 from us” when he acted on Israel’s behalf in a special UN committee dealing with the Palestinian refugees, whereas “last year he received only $500” for his actions in “the committee and the assembly.” In addition, Israel paid for him and his wife to receive medical treatment abroad.

The other members of the Liberian delegation to the UN also helped Israel. As Hanan Aynor, director of the Africa Desk, wrote in January 1970, “Of course, all of this is not being done only for the sake of heaven.” As an example, Aynor noted that he had succeeded “in canceling a debt of $5,000” for a high-ranking diplomat. In another case, the Israeli delegation to the UN arranged a job for the wife of a Liberian diplomat, even though, one of them noted in a cable, “unfortunately he is a flagrant drinker and is unreliable.”

Israel also assisted yet another Liberian diplomat who held a senior position in the UN, as she “is among our definite friends.” “We have promised to assist her with her plan to establish a commercial business for herself for income,” Aynor wrote in a cable. To that end, the Foreign Ministry funded a commercial survey in Liberia to help prepare the ground for the diplomat’s plan to establish a chain of department stores. Knowing this was irregular, the ministry sought to conceal its role in financing the project. “This is aid to a central personage in her private business, and if it gets out that the aid was provided by our authorities, that [information] could be used against us.”

The corruption did not end with diplomatic representatives. A number of private Israeli companies operating in Liberia were involved in corrupt and wasteful projects, including exploitation of the country’s forests, and in construction and infrastructure projects, as well as in drilling for oil. Hundreds of cables reveal that Israel’s Foreign Ministry not only knew about these ventures but also assisted financially and politically in closing certain deals and presenting this activity as an integral part of the Israeli government’s official civilian aid to Liberia. In certain cases, Israeli entrepreneurs were business partners of ranking officials in the Liberian government.

For example, even though Liberia was constantly on the brink of insolvency, a large Israeli development firm erected magnificent official buildings in the country, including the presidential palace and one of West Africa’s most luxurious hotels. In a cable dated January 1963, Ambassador Schiff stated that he had tried to persuade the company to build a sewage and water system instead of fancy buildings, “which the majority of the residents don’t need.”

The presidential palace, which was built with the aid of a $3 million loan from the Israeli government – even though it was clear that the money would never be repaid – was especially luxurious, so much so that even members of the foreign diplomatic corps were impressed. “We gathered in the large and magnificent reception room, with dozens of waiters dressed in white serving sandwiches and drinks in gilded glasses,” Ambassador Nahum Esther wrote following his visit to the building in 1965. “We went up to the fifth floor, where the luxurious dining room is located, its ceiling all made of glass… The food was served on gilded plates.”

Israel didn’t help only with money. When President Tubman wanted a brass band for his remote hometown in order “to endear himself to the inhabitants,” he contacted the Israeli embassy, which provided him with an Israeli conductor, too.

One of the corrupt projects in which Israel was involved was the creation of a youth movement, ostensibly to resemble Israel’s Nahal military brigade, which combines army service with civilian activity. The emissary who managed the project in Liberia warned in March 1970 that the movement “has no activity or content, and effectively has existed for some time only to dispense salaries to people.”

Israel also sold military hardware to Liberia, including rifles and machine guns, and aided the regime in its internal oppression. The Mossad, for example, helped Tubman establish an internal security service and trained its personnel to carry out routine security functions, to act as bodyguards for VIPs, conduct criminal investigations and thwart subversion. Corruption was not lacking there, either. According to a cable sent in November 1964 by Ambassador Schiff to the head of the Africa Desk, the internal security chief pocketed half of the service’s budget. As a result, he “doesn’t have any way to pay for fuel for the [service’s] vehicles. He is firing people and continues to receive their salary, which he transfers to his accounts in different banks.”

The relations between the two countries started to unravel after Tubman’s death, in July 1971. His successor didn’t trust the serving heads of security, who had maintained close ties with Israel, and finally replaced them with his own coterie. Israel’s status in the country plunged. In November 1973, Liberia joined the dozens of countries in Africa that severed their ties with Israel, citing the Yom Kippur War as a pretext. Relations between Israel and Liberia were not renewed for about a decade, when the military dictator Samuel Doe came to power.

In April 1980, Doe, who was serving as a sergeant in the army, staged a brutal coup. He executed the serving president, William Tolbert, as well as dozens of other high-ranking government officials, and threw hundreds more into prison. The Israeli legation in Monrovia reported that Doe was also having detainees executed in the prisons.

From then until its ouster, a decade later, Doe’s regime was known for making broad and systematic use of torture, for disappearing people, carrying out executions without trial, imprisoning opposition leaders and severely restricting freedom of expression. Liberia became a leper state in the eyes of most other African nations, and the U.S. Congress limited financial and military aid to the country, exacerbating what was already a grim economic crisis.

The Israeli government saw this as an opportunity to renew relations with Liberia. Doe, after all, was isolated and had nothing to lose. It was the height of the Cold War and Washington, too, didn’t want to forgo ties with Liberia. Thus, while Congress was imposing sanctions on the country, the administration looked for indirect ways to preserve its interests in Liberia. As in the case of the Iran-Contra affair (when Israel served as a conduit for the sale of U.S. weapons to the Islamic regime in Tehran, as well as passing the payments on to right-wing rebels in Central America), Israel took it upon itself to fill the shortages in the Doe regime’s security needs, which the Reagan administration couldn’t itself supply directly.

Contacts to renew relations began in 1982, but were unsuccessful, because leading members of Doe’s military junta preferred the support of the Arab states and of the Soviet Union. The solution was found at the beginning of 1983. According to a series of cables, Israel’s representative in Ivory Coast, Benad Avital, who represented Israel in contacts with Doe’s regime, got a request to pay off five ranking figures in the junta in return for their support in renewing diplomatic relations with Israel. The five demanded a payment of $25,000, which was to be split between them.

A dispute arose over whether to pay the bribe up front or only after the full restoration of relations. A compromise was reached, by which $6,000 was paid in advance, and after the necessary authorizations were received in the Foreign Ministry, the rest of the money would be forwarded.

It wasn’t only a lone cash payment. A cable sent by Avital to the financial department of the Foreign Ministry referred to the initiative as “Operation Gifts.” Among other requests, he sought reimbursement for a briefcase he had bought the Liberian army chief of staff for 30,000 West African CFA francs (then worth about $50). He had also promised the army chief “a gold Star of David, a Hebrew-English Bible and a visit to the Holy Land at Israel’s expense at a time of his choosing.”

In an April 1983 cable, Avital suggested completing payment of the outstanding $19,000 of the bribe, explaining that “the requested sum is not large as grease for the wheel of important business.” The Foreign Ministry wasn’t sure how to proceed, and decided to consult with the United States. In the end, with the mediation of the American ambassador to Liberia, Israel managed to arrange a meeting with Doe. At this stage, Israel stated that it was refusing to pay the rest of the bribe, because the task had been accomplished through the U.S. ambassador. Indeed, about a month later, Doe announced the resumption of diplomatic relations with Israel.

Following this development, combined with Liberia’s renewed support for it in the UN, Israel, in coordination with Washington, renewed its aid to the country’s security forces, which were responsible for the domestic suppression. According to the cables, Israel decided to send a delegation to Liberia to survey the situation ahead of establishing and training a unit to combat guerrilla warfare. Israel also decided to supply the junta with a gift: ammunition worth $100,000 to $200,000.

In August 1983, Doe visited Israel, accompanied by an entourage that included the entire top ranks of the junta. They met with the prime minister, Menachem Begin, and with representatives of the Mossad, and visited military industries. During the visit a deal was struck with what was then called Israel Aircraft Industries for the purchase of four Arava transport aircraft by Liberia, and it was agreed that Israel’s national carrier, El Al, would provide Liberia with two Boeing 707s in return for a maintenance services agreement with the airline. Following the visit of a Mossad’s team to Liberia, an agreement was reached under which the Israeli agency would establish and train a special force to guard President Doe and train police forces to deal with domestic disturbances.

The Foreign Ministry cables reveal that the Mossad and the Israel Defense Forces established one of Doe’s most murderous units, know as the Special Anti-Terrorist Unit (SATU). Its extensive and systematic violence is considered one of the major causes of the public ferment against Doe’s regime and for the country’s slide into civil war in 1989.

The unit’s creation is mentioned for the first time in a cable sent by the director of the Africa Desk, Avi Primor, in January 1984. The document stated that the ammunition shipment had already left Israel and that Mossad representatives in Monrovia were preparing a plan to form a special anti-terrorism unit. A cable sent a year later by the ambassador to Liberia, Gavriel Gavrieli, noted that a “highly successful” training course of 17 members of the unit’s commanders had “just now” ended. “We are about to send instructors of ours to assist them in forming the [army] company,” Gavriel wrote and added that the company members had received personal weapons “as a gift, according to their request.”

The two planes that El Al handed over proved an embarrassment. The ambassador reported that they had been found to be “almost unworthy of further use, which is why El Al couldn’t get rid of them.” The Liberians, Gavrieli reported, felt “not only cheated, but what is worse, they feel they have been mocked.” The deal for the Arava planes, which were intended to fly soldiers within the country in the event of an uprising, also turned into a farce. Even though Israel trained 15 pilots, Liberia was able to make only one down payment, of $600,000, out of a total of $8 million. As a result, only two of the four planes were delivered, and when the door of one of them ceased to function and was sent back to Israel for repairs, IAI refused to send it back, rendering the aircraft non-operational.

Concurrently, pressure by the U.S. Congress increased to condition aid to Liberia on its transition to a civilian regime. Doe also tried to leverage this into payment of bribes. Dozens of cables reveal that he asked Israel to pay $20 million to 17 junta members who were his partners in power. He claimed that these individuals were preventing him from setting up a civilian regime and that the money would allow them to leave the country and take up studies in the United States under “VIP conditions.” Doe warned that if their palms were not greased, they would stage a coup against him and would act to break the ties with Israel. Instead of $20 million and studies in the United States, Israel was ready to pay for tractors for them so that they would be able to work their land in Liberia. The Liberian ambassador did not accept the Israeli proposal.

Together with the renewal of the diplomatic and security ties, in 1983, the private Israeli companies also resumed their activity in Liberia, with Foreign Ministry assistance. The companies’ projects included the construction of more luxury buildings for the government and operation of franchises to exploit and cut down forests in the country for decades to come.

In November 1985, in the wake of allegations about the falsification of election results in the country, a coup attempt was staged, led by the former chief of staff. A series of cables reveal that Doe anticipated the insurgency, because of the elections, and asked Israel to strengthen the security forces and the police in advance. Israel helped, sending advisers on intelligence and on counterterrorism, and local 150 police officers underwent a crash course on dispersal of demonstrations. Israel also supplied tear gas. The deployment paid off, and Doe believed that Israel had saved him. Israel’s ambassador to Liberia at the time, Arie Ivtsan, a former police commissioner, reported Doe as remarking that it was “only thanks to the Israeli ammunition and assistance that he remained in power.”

In a meeting held in Jerusalem two months later, Foreign Ministry officials summed up Israel’s success in preventing the coup. According to the minutes of that meeting, the Israeli embassy in Monrovia reported that the opposition was indeed correct: The election had in fact been rigged. “In an unofficial count of the votes, the opposition won 65 percent,” it was written in the minutes, “but the ‘corrected’ official count left power in Doe’s hands.” According to the embassy, the rebels had fought “incompetently,” whereas “SATU, which was trained by Israelis, operated with self-confidence… Similarly, the police, which also underwent Israeli instruction, preserved public order efficiently.”

The Israeli embassy also reported on the human cost of the events: Doe executed hundreds of people. According to a report by Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was established in 2005, the former chief of staff, who led the coup, was murdered, and his body was eaten by Doe loyalists. The tyrant launched a campaign of collective punishment and massacre against the general’s ethnic group, spearheaded by SATU.

The Doe regime’s oppression became more severe in the years that followed. Dozens of Foreign Ministry cables describe the brutal violence of the special ops units that were trained and armed by Israel. They carried out mass arrests, torture and the murder of opposition activists, demonstrators, journalists, teachers, physicians, students, rival ethnic groups and even just civilians who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. The cables also mention the political persecution of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who was then one of the leaders of the opposition, because of her public criticism of human rights violations in the country.

Israeli Foreign Ministry representatives in Liberia and in the United States reported to Jerusalem that the Liberian opposition was critical of Israel’s involvement in the domestic suppression. In a meeting in Washington with representatives of the Liberian opposition, including members of Sirleaf’s party, officials of the Israeli embassy were told emphatically that the perception among broad circles in Liberia was that “Israel constitutes Doe’s main security prop,” including aid to what they termed “death squads.”

Despite having clear knowledge of the untenable human rights situation in Liberia, Israel continued to train and arm the country’s security forces as usual, in coordination with and knowledge of the administration of Ronald Reagan. The tour of duty of the special Israeli advisers to the domestic security service (from the Mossad), the police (from the Israel Police) and the counterterrorism forces (from the IDF) was renewed each year. In June 1987, Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir visited Liberia and met with Doe. The Foreign and Defense Ministries approved gifting SATU with sniper rifles, and more tear-gas grenades were sent to the police.

With the knowledge of the Foreign Ministry, Israeli companies also continued to be involved in corrupt practices. A top figure from Doe’s regime was a salaried employee of an Israeli firm that received a license to cut down forests. Another Israeli company succeeded in obtaining a permit to fell forests in a vast region in a different part of the country, after promising to provide as a “gift” to SATU of the jeeps and military equipment it lacked.

The bitter end was a tale foretold. On Christmas Eve in 1989, the warlord Charles Taylor invaded Liberia at the head of a group of rebels and triggered a bloody civil war that some years later led to Taylor’s conviction on charges of crimes against humanity. Doe was captured by rebel forces on September 9, 1990. Following 12 hours of torture, captured on video and broadcast, he was executed and his naked body was displayed in the streets of Monrovia.

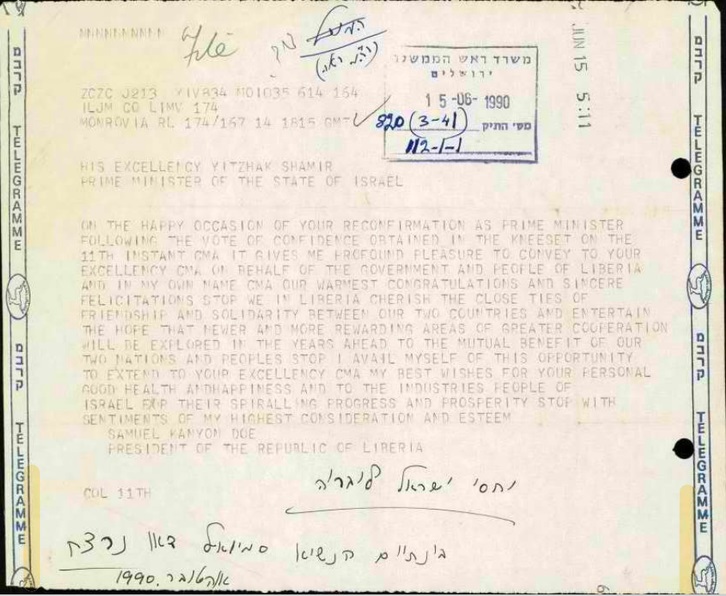

In June 1990, a few months before that incident, at the height of the civil war and amid atrocities he himself was committing, Doe found time to send a personal cable to Shamir, to congratulate him on becoming prime minister again. This time Shamir chose not to reply. At the head of the cable, the director general of the Foreign Ministry added by hand, “Seen by the prime minister.” Below, he wrote, “In the meantime, President Samuel Doe was murdered. October. 1990.” Source: haaretz.com