Observers expected fraud in Liberia’s October 10 elections, but its extent shocked even those who had witnessed hundreds of polls. President George Weah may believe he can silence Liberians long enough to steal a second term. He may even think that, midway through a second term, he can hold an equally fraudulent referendum to dispense with term limits entirely, much like Central African Republic President Faustin-Archange Touadéra.

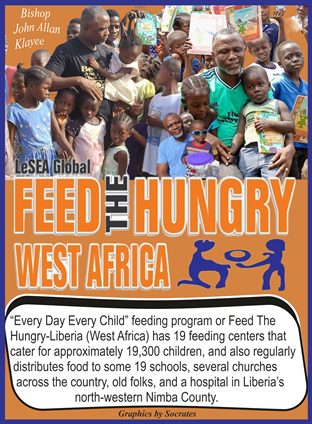

If Liberians remain silent, Weah could become president for life. He could continue to use Liberian resources to live large in Qatar, Monaco, and the French and Italian Riviera as ordinary Liberians go hungry.

The reality, however, is that the pain Liberia will suffer if Liberians remain silent in the face of Weah’s fraud will be larger. Mali was once West Africa’s most vibrant democracy. It per capita income grew 400 percent between 2000 and 2020, when it suffered the first in a series of coups. Its per capita has since declined every years and shows no sign of stabilizing. The same pattern also applies to Burkina Faso.

Countries which international organizations rank highly corrupt also are among the world’s most impoverished. In Africa, this is the case with Somalia, Eritrea, Burundi, Chad, and Guinea. Even oil-rich countries like South Sudan or Azerbaijan show deep poverty on a per capita basis.

Azerbaijan is an important case study, even if it is not African. It sits on hundreds of billions of dollars of hydrocarbons. British Petroleum, which partners with the state oil company, has paid billions of dollars to Ilham Aliyev’s regime. Neither neighboring Armenia nor Georgia have oil and gas, and yet the citizens of these countries enjoy higher standards of living because their governments do no embezzle wealth. Within Africa, Rwanda’s efforts to defeat corruption have led to steadily increasingly living standards in that tiny Great Lakes country, especially compared to neighboring Burundi and Uganda.

In 1992, Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori staged an autogolpe [self-coup] to ensconce himself in power. What followed over the next eight years of his rule was relative stagnation, especially compared to peer states like Mexico.

Weah may try to use the strategy employed by Eritrean dictator Isaias Afwerki to distract attention from his failures: Try to claim that any criticism of his corrupt and dictatorial rule is akin to Western colonialism and an affront to nationalist pride. Liberians should not accept that nonsense. Liberians have agency. They have free will. The “African solutions for African problems” mantra does not mean acceptance of incompetent, corrupt governance. After all, Namibia, Botswana, Ghana, and the Côte d’Ivoire each show that democracy works while Rwanda, whatever its democratic deficit, also shows how countries can achieve their potential when they tackle corruption.

The simple reality is that no investors want to lose money. There is a reason why big firms station themselves in South Africa, Rwanda, and the unrecognized Republic of Somaliland, but avoid their neighbors oike Mozambique, Burundi, and Somalia proper.

Liberians must prepare for being treated like pariahs and rogues similar to Eritreans. Western countries might target sanctions narrowly against Weah, Monrovia Mayor Jefferson Koijee, Commission chair Davidetta Browne Lansanah, or Weah placeholder Edward Appleton, but such sanctions always impact ordinary officials. If Liberians accept a fraudulent election, they are complicit in the fraud. They may expect a series of ratcheting sanctions that will make it near impossible to gain visas to Europe or the United States, or receive remittances from relatives in those places.

The worst-case scenario, of course, would be an unraveling of the fabric of society in the way that leads to a new civil war. Liberians of all political backgrounds need to ask: Do they want to return to the era of Samuel Doe and Charles Taylor, or do they want to embrace a new, more prosperous era that puts the welfare of all Liberians above that of a single president?

Michael Rubin is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC.

This is a perfect analysis of what Liberia, under clueless, inept and extremely corrupt ex-footballer, George Weah is, and will become if Liberians sit home supinely instead of going to vote massively against him in the runoff, and chase him out if he tries to thwart the will of the people by trying to rig the elections.